Jack Smith's Obituaries

"Jack Smith is gone. Los Angeles is a widow." Francophile Jan C. Gabrielson, 1996, upon hearing of the death of Jack Smith and without apologies to Georges Jean Raymond Pompidou, President of France

![]()

Wednesday, January 10, 1996

Jack Smith,

Urbane and Wry Times Columnist, Dies

Journalism: Self-effacing writer was 79. His musings on daily

life entertained readers for nearly 40 years.

Main News, Page A-1

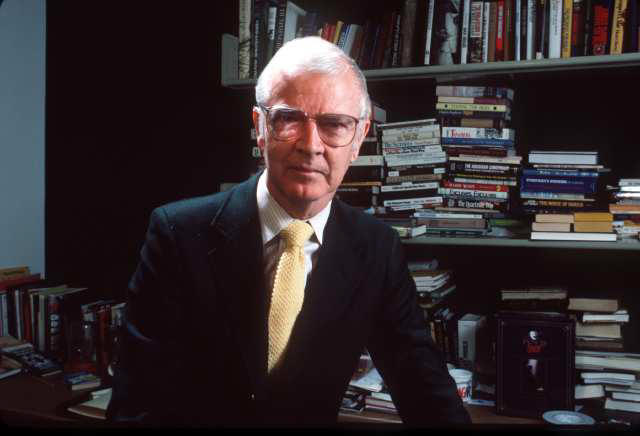

Jack Smith in

1985

LARRY ARMSTRONG / Los Angeles Times

From a Times Staff Writer

Jack Smith, whose urbane Los Angeles Times column dealt gently with his

absorption in almost everything and everybody around him, died Tuesday

of severe heart failure.

Smith, 79, died at USC's University Hospital in Los Angeles. He had

weathered more than a decade of heart disease, including quadruple

bypass surgery in May 1984 and a heart attack that December, another

heart attack after prostate surgery more than two years ago, and yet

another heart attack in late December.

"There will never be another Jack Smith," said Otis Chandler, former

publisher of The Times, who had befriended Smith when they both were

reporters in the 1950s. "Over his long and distinguished careers as

first a reporter and then a columnist for The Times, he has brought a

unique flavor to the paper that cannot be duplicated.

"In many ways," Chandler said, "he was like a Will Rogers in the way he

could make almost any subject funny and interesting and instructive."

Times Publisher and Chief Executive Officer Richard T. Schlosberg III

said Smith's "impeccable use of language and his gentle, urbane style

were flawless, and yet his manner was one of humility and great

kindness. He observed and wrote about everyday life with humanity and

humor, turning phrases with a style that is unmatched."

Smith's column "has been one of the abiding highlights of the Los

Angeles Times," said Editor and Executive Vice President Shelby Coffey

III. "The column expertly reflected the key qualities that made the man

beloved as a writer and colleague; it had sly elegance, genteel

self-mockery and keen observations of the life he loved in

ever-surprising Southern California."

To say that "the saga of Jack Smith, told over these many years in the

pages of this newspaper, will be missed is to sadly understate our

loss," said former Times Editor William F. Thomas.

"Jack wrote with unfailing grace and clarity, and did so with amazing

consistency," Thomas said. "His simple prose, unassuming and yet

pointed, appeared effortless, but it was the result, like all fine

writing, of very hard work.

"Most of all though, was this: It was throughout a candid and funny and

touching chronicle of his own life and, in these last months, of his

approaching death."

San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen said Smith "was just like

his writing: slightly crotchety, a bit put off by what is going on,

always ready for an argument, extremely dry in the wit department--and

yet, altogether lovable. As a columnist, obviously one of a kind."

Smith's column, which had appeared in The Times since 1958, was

distributed to almost 600 newspapers worldwide by the Los Angeles

Times-Washington Post News Service. After about 6,000 columns over 30

years, bowing only slightly to declining health, Smith cut back in 1992

from four columns a week to one, which appeared on Mondays. For most of

his career, he wrote five columns a week.

"I may," he warned, "turn senile overnight."

His use of the language was meticulous, his manners were graceful--both

in print and in public--and his middle-aged fascination with the trivia

of a changing world was a constant delight to his readers.

He could amuse them or stir a few to irascible letter-writing with a

column on his lifelong wariness of cats. He could reduce them to idle

daydreaming by a bit of nostalgia out of his pre-World War II days

working his way to Hawaii on a passenger ship to write for the Honolulu

Advertiser, or a piece about his rustic house on a remote Baja

California seaside cliff.

"When we reached the house," he wrote in one of his "Baja Diary"

columns, "the rain had stopped, but the wind off the ocean was like wild

organ music in the roof tiles. We lighted lanterns and I built a fire;

that is to say, I put an ersatz log from the supermarket in the grate

and put a match to it."

Smith was never dishonest enough to pretend that he had left all traces

of civilization behind. He never seemed to be in awe of his own

considerable talent and he could be self-deprecating without phoniness.

He resented the presence on the planet of very few, and he was never

cruel.

It was the Baja house columns that in 1974 formed the basis for his book

"God and Mr. Gomez." His other books included "Three Coins in the

Birdbath" (1965), "Smith on Wry" (1970), "The Big Orange"(1976), "Jack

Smith's L.A." (1980), "How to Win a Pullet Surprise" (1982), "Cats, Dogs

and Other Strangers at My Door" (1984) and "Alive in La La Land" (1989).

The columnist's love for the language with all its traps and

inconsistencies led him to conduct charming written debates with college

professors or elementary school children, treating each with equal

courtesy and respect for personal opinions.

For all his intellectual concerns, Smith cared as much for some of the

more earthy aspects of American culture. Pro football, for instance:

"Intimate friends know," he once wrote, ". . . that my love of football

is not simply visceral. I see it as a more dynamic form of ballet."

He was one of the few newspaper columnists who could write about the

minutiae of daily family life without seeming desperate for material.

His humility as the man of the house on Mt. Washington near downtown Los

Angeles never had a fake ring to it. Readers came to know his wife,

Denny (rarely mentioned by name); his sons, Curtis and Douglas; his two

daughters-in-law, Gail and Jacqueline, and five grandchildren, Chris,

Casey, Trevor, Adriana and Alison.

But he insisted when he went into semi-retirement in 1992: "I'm always

the butt of the jokes. I am the joke in this family. I'm just trying to

be amusing. About the only person you dare to make fun of is yourself."

He also wrote about a succession of dogs and cats, which he tended to

describe in terms of their personalities (a word he may well have

accepted in their cases) or levels of intelligence.

In discussing an old cat named Gato that had run off, Smith wrote: "I

don't know why it is that I have so little luck in developing a warm

relationship with cats, especially when so many men I admire very much

have been fond of cats."

Revered in his profession, Smith received the Joseph M. Quinn Memorial

Award, the highest honor of the Greater Los Angeles Press Club, in 1991.

He occasionally joked that he had come close to winning a Pulitzer Prize

but that "one can't talk about having won second place in the Pulitzer

Prize."

Although Smith was the recipient of various honorary degrees from

universities, his formal education ended with his attendance at

Bakersfield College. His real education was received in the Civilian

Conservation Corps during the Great Depression, in the scullery of that

passenger liner, as a Marine Corps combat correspondent under fire on an

Iwo Jima beach in World War II and on a succession of newspapers that

began in the 1930s with the Bakersfield Californian, where he was a

sports writer.

Perhaps it is not accurate to say that his newspaper career began there,

for in the biographical information he long ago submitted to The Times'

public relations department, he noted that he was the editor of the

student newspaper when he attended Los Angeles' Belmont High School and,

as only Jack Smith could, pointed out that it was the highest position

he ever reached in his career.

Before he came to The Times as a general assignment reporter in 1953,

Smith worked for the Honolulu Advertiser (often recalling in later years

that he had "passed" on the story of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

because he was just getting to bed after a late Saturday night party and

was not clear on what was going on), the United Press, the Sacramento

Union, the San Diego Journal, the old Los Angeles Daily News and the Los

Angeles Herald-Express.

He walked with the erectness of an ex-Marine, to be sure, always trim

and neatly dressed. He usually wore a tie, correctly knotted. But there

generally was a casual touch--perhaps a sport jacket easily visible at

some distance, or a Greek fisherman's cap.

If he talked at all about his time in the Marines, it was to recount the

violent assault on Iwo Jima. He went ashore as a combat correspondent,

with his rifle but without his portable typewriter.

A colonel suggested "that I send my typewriter in his jeep, which was

scheduled to go in the eighth wave," Smith wrote. "The boat was sunk. I

never saw my typewriter again."

The regiment's other combat correspondent, a Marine named Barberio, "had

gone by the book" and carried his typewriter ashore. Barberio was killed

in the invasion, but a Marine found his typewriter and gave it to Smith.

"I used my knife to open the case," Smith wrote. "There was no

typewriter in it. It was full of canned goods.

"That's what war is like. Only a thousand times worse."

Although Smith's boyhood roots were generally in Bakersfield, he was

born in Long Beach on Aug. 27, 1916.

After some time in the Civilian Conservation Corps, he went to sea at

the age of 21 and remarked in print later that the merchant marine "was

the only other kind of work, besides newspapering, that I might have

been happy in."

But it was newspapering he went into, earning a reputation as a

sensitive, facile writer in those days of street-edition sensations, low

pay, hard work and hard-drinking reporters and rewrite men.

Among the street-sale sensations he worked on was the so-called Black

Dahlia case soon after World War II. In fact, he probably coined the

sobriquet for the brutally murdered young woman, despite claims of

credit by others.

His newspaper jobs never seemed to last very long. Smith, like others of

the era, had itchy feet. It was not until he came to The Times in June

1953 that he settled in. He began to write humor pieces for the op-ed

page and before long was appearing regularly as a columnist.

Among his running topics was his fondness for watching the birds on the

canyon hillsides of Mt. Washington. It was his contention--despite the

protests of experts--that he was the first person in California to spot

a grackle.

"It was unbelievable, of course," he wrote, "and nobody believed me. I

was soon vindicated, however, by a second sighting. This one again took

place in my backyard and nobody believed me again."

Nevertheless, something called the annual Jack Smith Bird Walk was

instituted at Descanso Gardens.

As he grew older he took a patriarchal view of Los Angeles, defending

the city in print against those who considered it a refuge for

Philistines while speaking pridefully of it in private. One pleasant

fall afternoon, as Smith watched USC and UCLA battle each other for the

rights to the Rose Bowl football game, the blimp taking aerial

photographs of the spirited contest flew over downtown, televising a

panoramic picture of majestic skyscrapers framed by plush mountains.

"There is a there there," said Smith in a barely audible paraphrase of

Gertrude Stein.

His last column appeared in The Times on Christmas Day.

Following Smith's wishes, there will be no funeral service. A public

tribute to be organized by The Times is pending.

Donations can be made to the Jack Smith Memorial Trust, a fund created

by his family to support things that meant most to him: newspapers,

libraries and Southern California culture.

***********************************************************************************

BILL BOYARSKY

Jack's Last--and Toughest--News Story

By BILL BOYARSKY,

When Jack Smith began writing columns about his long, final illness, I

had trouble accepting the change from his usual amusing tales of life on

Mt. Washington.

I discussed this with a mutual friend, retired Times Editor Bill Thomas.

"You don't understand," Thomas replied. "He's covering his own death."

And Jack was doing it, Thomas explained, just as he had covered

everything else--with precision and a clear eye. No sentimentality or

self-pity cluttered up his last story.

From then on, I read the columns with care, as Jack chronicled the

failures of a body that now needed the assistance of his wife, Denny,

and others to get around town. Step by step, each stage of deterioration

was reported.

It was not a lonely, despairing death that he recorded. As always, Jack

was surrounded by family and friends, the cast of characters we'd come

to know, supplemented by newcomers, nurses, therapists, doctors and

others, each of them captured by Jack's undiminished ability to describe

people.

Reading these columns, I thought about my elderly parents' long decline,

and their deaths, first my father and then my mother a month later.

Jack's column reminded me that my family was not alone in our

experience. A colleague told me that many people wrote the paper to say

they felt the same about Jack's columns.

*

I first met Jack 25 years ago when he was a rewrite man, working in the

Times newsroom. He took the notes from field reporters and turned them

into stories, as well as going out on interviews and to events himself

and writing about them.

He was part of a cynical, hard-drinking generation of reporters who made

fun of politics, love and death. The newspaper--and the nearby bar--were

the centers of their social and professional lives. Standing at the

pinnacle of this cloistered society was the rewrite man, and Jack was

the best in town.

He was friendly to me, especially after learning I had just come down

from Sacramento, where I had worked for the Associated Press. Jack had

been on the Sacramento Union staff for a time, and we exchanged stories

about that paper and the ratty old bar, the M Street, where the

reporters and printers drank.

In those days, Jack wrote his column part time, most of his energy going

to the rewrite chore, a skill he had honed at the now-dead

Herald-Express and the old Los Angeles Daily News. It was at the Daily

News that Jack had what he called "my finest hour as a newspaperman."

The body of a nude woman, sliced in half, was found in a vacant lot.

Working the phones, Jack found a Long Beach drugstore frequented by the

woman, Elizabeth Short. Sure, said the pharmacist, he remembered

Elizabeth Short. "They called her the Black Dahlia--on account of the

way she wore her hair," he said.

Writing about it years later, Jack said: "The Black Dahlia! It was a

rewrite man's dream. The fates were sparing of such gifts. I couldn't

wait to get it into type."

Jack treasured his skill as a rewrite man, but his editors, impressed

with the style and popularity of his column, wanted him to become a

full-time columnist. Times reporter Eric Malnic recalls that Jack was

reluctant to make the switch, fearing he couldn't cut it.

But luckily the editors prevailed, and Jack was soon turning out daily

columns.

He was a master of the form.

Jack followed the journalistic formula of short sentences and compressed

paragraphs. His writing teachers were not professors but tough veterans

such as Hemingway and Aggie Underwood, city editor of the

Herald-Express. But with his natural ability, he took the formula and

turned it into subtle and witty prose. When I asked him how he did it,

he seemed surprised that I considered the work so difficult. Like the

great quarterbacks he admired, Jack made the daunting task look easy.

To us pampered columnists of today, who think two or three a week are

exhausting, the Smithian pace was astounding.

To sustain it, Jack couldn't waste a second.

That was obvious when my wife and I were at parties with Jack and Denny.

He was a charming, witty raconteur and was usually surrounded by a large

number of women and men intent on catching every word. Two days later,

we would find in his column the same delightful story he had related at

the party.

*

Family, friends, football, vacations, his entire life were the subjects

of his columns.

His readers shared this life. They were members of the post-World War II

generation that filled the Southland's subdivisions and schools, built

swimming pools, raised kids, supported the public library, watched

football and went to the philharmonic.

In the last several months, his readers shared his death. Some of them,

nearing death themselves, may have taken a special comfort from his

columns.

This was Jack's toughest story and, in covering it, his greatest gift to

his readers.

***********************************************************************************

An Eye for

Simple Pleasures in a Complex World

Main News, Page A-12

The world of Jack Smith ranged from the front porch of his much-maligned

hideaway in Baja California to the birdbath at his Mt. Washington home.

But regardless of the geographic vantage point, he found humor, poetry

and gentility in a world he viewed with a fey imagination.

A final tour of a few of the vistas of Jack Smith:

On attending the 50th reunion of his Belmont High School class and

explaining why it was better than the 25th:

"[The 25th] catches everyone at midlife crisis. It throws vulnerable

people together in a kind of brutal encounter at a moment when they are

already abraded by regrets, bewildered by uncertainties, and tormented

by resurgent fantasies.

"Women are anxious about menopause and fading beauty, about empty homes

and errant husbands; men look in the mirror and no longer see Charles

Boyer or Charles Atlas. Jealousies are sharpened; spouses measure their

mates against the ones that got away; infidelity is contemplated if not

accomplished, and almost everyone goes home only slightly disenchanted."

But after 50 years "we have banked most of our fires; our passions are

subdued; our regrets blurred, our demons exorcised. We are rather

surprised to be here at all, and not entirely discontented."

*

Of his quadruple bypass surgery in 1984 and the mysteries that

accompanied that life-threatening procedure:

There was a "fantasy [that] took root somehow during my deep anesthesia,

when they had stopped my heart and I was running on a machine." He

imagined he was "the victim of an insidious international ring of

kidnappers," and then, the operation over, "I began to write on my

computer. Endlessly. Pouring out pages of exposition so articulate, so

balanced, so illuminating that I knew I could never repeat them."

*

After his many bouts with heart problems, he frequently wrote of those

who had nursed him back to health:

A nurse--"I knew that face: fair, pleasant, reflective, modestly

voluptuous. Suddenly it came to me. She was the girl in the French

Impressionist painting--the bartender at the Folies Bergere." His

cardiologist--"who speaks with a gentle Southern inflection that seems

to make even bad news sound rather pleasant."

*

When in near-normal health, he continued his travels around Los Angeles,

a journey that at first spanned 25 years as a working journalist and

even longer as columnist and author.

Dressed in a tuxedo, he attended the opening of the French Impressionist

exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. But the stylish,

catered affair was crowded so that Smith and his wife slipped away to a

nearby fast-food restaurant:

"Actually, my Big Boy's tuna sandwich wasn't all that bad."

*

And then, shaking off apprehension about the steep stairs in the Los

Angeles Coliseum, he attended the opening of the 1984 Olympic Games,

sitting not far from where he sat 52 years earlier, when the 1932

Olympics had opened in the same stadium:

"I'm glad I went. I'm glad I live in Los Angeles. I'm glad I'm an

American.

"I'm glad, come to think of it, to be alive."

*

He remained true to his dedication to simplicity in all things, even the

epitaph he asked for himself. It was to say only:

"Have a nice day."

***********************************************************************************

ESSAY

Jack Smith and L.A.'s Backyards

By ROBERT A. JONES,

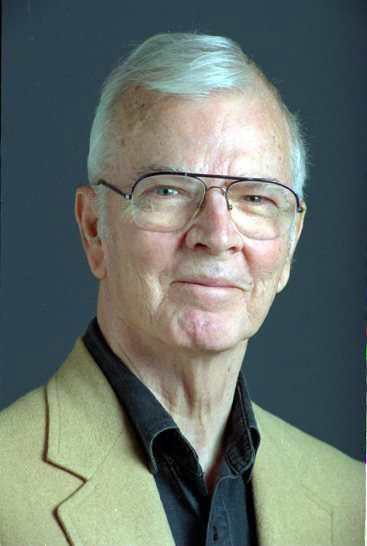

JACK SMITH, semi-retired columnist, 1995: In many ways, Jack served as the country's first--and most enduring--columnist of postwar suburbia. With his minimalist, non-intrusive style he fit superbly with his era.

I had a friend back in the '70s who published a small magazine in West

Hollywood. This magazine was the sort that delivered high attitude and

regarded itself as a cool piece of work. Anyway, my friend always

claimed you could divide Los Angeles into two groups of people: Those

who "got" Jack Smith, and those who didn't. Personally, he didn't.

I remember one time at lunch he produced one of Jack's columns and read

parts of it to me. The column described some patio paving or barbecue

building at Jack's house on Mt. Washington. The work had hit a few

snags, as it always did in Jack's universe, and there were also some

problems with the dog. I recall the dog trying to walk on wet concrete.

The editor looked at me. "See what I mean?" he said. Where was the

political commentary? The leg-biting anger toward our civic leaders? He

rested his case.

Jack Smith died Tuesday. For what it's worth, he out-lived and

out-worked my friend's magazine by some 15 years. But on the day he

died, you could still make the same observation about Los Angeles: The

city was divided into those who "got" Jack Smith and those who didn't.

Not to say that the Jack Smith question provoked fistfights on street

corners. Jack himself remained far too civilized and full of good humor

to raise blood passions. Rather, among the constituency of newspaper

readers in the city, people simply knew where they stood. Either you

appreciated the grand message behind his talk of carpenters and TV

trays, or you were left baffled.

Jack's message came down to this: Los Angeles operates under rules that

are different from other cities.' Perhaps you can find the soul of New

York or Chicago on the sidewalks, but not here. Los Angeles has an

interior life that is private and hidden from view. L.A.'s soul can be

found behind the hedges, in its backyards and patios, around the

barbecues.

And where other cities build communally, L.A. builds individually.

Everyone here constructs their own universe behind their own fence. Like

all great columnists, Jack understood that crucial difference between

his city and others, and he exploited it to the full.

He filled his column with his family rather than the mayor and his

henchmen. The children fell off ladders and broke their arms, grew up,

married French girls. Jack bickered over the selection of TV dinners.

The bathroom got remodeled, the patio grew a little more grand.

Though he took an occasional auto tour with his wife, Jack's life always

seemed circumscribed by the boundaries of his property and the interior

of his car. That's how life goes here, Jack was saying. And he was

right.

*

Of course, there was also the house in Baja, the weekend getaway that

consumed years in construction. In many ways, the Baja cabin simply

functioned as a proxy for the house on Mt. Washington, except that it

also produced Mr. Gomez, probably the greatest character in Jack's

repertory.

Gomez owned the Baja property, had little formal education and did

things his own way. Jack and Gomez did not share a common language or

even a common view of the way the world worked. In their bafflement at

each other, they epitomized the cultures they represented. Yet they were

forced to work together in building the cabin and eventually each

developed a deep trust and affection for the other. You wonder if such

things could happen today.

You also wonder if another Jack Smith could happen. I doubt it. In many

ways, Jack served as the country's first--and most enduring--columnist

of postwar suburbia. With his minimalist, non-intrusive style, he fit

superbly with his era. He functioned almost as a diarist of the time

when modern L.A. was being built.

But those days have ebbed away. L.A., in fact, no longer truly functions

as a suburban culture. It is something else, something in between

suburban and urban. When my friend, the magazine editor, suggested that

he did not "get" Jack Smith in the 1970s, he probably represented a

growing population. People who did not share the suburban dreams of

Jack's generation, who wanted their backyard barbecues but also wanted a

public life on the sidewalks.

*

In many ways, L.A. has given it to them. At its heart, the city remains

a haven of the interior life. Yet that life has combined with public

neighborhoods that leave L.A. looking curiously like a real city.

It was part of Jack's greatness that he never complained, at least

publicly, about the passing of those glory days. I suspect he found it

not sad at all but mostly interesting. Jack never had to own his city.

He continued, to the end, writing about the grackles he spotted from his

patio, about the remodeling project down the street, about the ads on

TV.

Also, most courageously of all, he wrote about losing his memory, about

the terror of being enclosed in an MRI machine, about life in a

wheelchair. He was telling us that he was dying, describing how the

process happened bit by bit, accompanied by technicians in white coats

and machines that hummed. He didn't like it but he kept writing because

he thought we might be interested. And if we "got" it, we were.

NOTE: Photos are uncropped archival versions and may differ from

published versions.

***********************************************************************************

Goodbye, Mr.

Smith

He wrote about it all. Column after column, year after year. Through

him, we got to know about the city we love most, about him, about each

other.

He Was Honest, Graceful, Wry -He Was Jack

Life & Style, Page E-1

By ROBIN ABCARIAN,

Many times, toward the end, I received the panicked calls from readers.

"Where is Jack Smith?"

"Is Jack Smith OK?"

"He's ill," I'd say. Or, "On a cruise. Don't worry. He'll be back. Jack

always comes back." That's what we thought anyway.

For a child of Los Angeles, who grew up to the thump of The Times on her

porch every morning, this page without Jack Smith is nearly

inconceivable.

Jack is and has always been. He was from some kind of mold they don't

make anymore. I sat at his feet at a Christmas party in 1994, asking him

about the old days at The Times. When he first became a columnist, he

said he was writing almost every day. Almost every day! It got so

exhausting, he said, that he finally pleaded with his editor, "You know,

I'm here so much, I bump into myself coming and going."

Ever so graciously, the editor allowed Jack to reduce some of his

non-column responsibilities.

At his peak, Jack was an extraordinary writer--graceful, agile, wry. I

admired that. But what I grew to love was the unflinching way he faced

his physical disintegration. He wrote it, and you felt it: the tedium

and terror of falling apart, of becoming dependent--and even worse--of

becoming a nuisance.

As his health worsened, he wrote of passing out at lunch; of throwing up

at the captain's table on a cruise ship. He wrote of bad moods and

hopelessness, but in a way that made you feel that here, in the City of

Eternal Youth, there is nothing shameful in growing old. Jack taught us:

Infirmity happens.

There's another thing I loved about Jack--in the age of abstinence,

12-step programs and sorry public confessions, here was a man who adored

his cocktails and wasn't afraid to admit it. He wrote lovingly of his

vodka-and-tonics, of his glasses of white wine; he wrote irascibly of

those who would deny him their glow. Here was a man, rare today, who

never in his life apologized for taking a drink. At least not in print.

And so we toast Jack Smith today.

It's going to be a long, sad hangover.

Master of the Loneliest Job in Journalism

Life & Style, Page E-1

By PAUL DEAN, TIMES STAFF WRITER

The last time I saw him out of a wheelchair, he was sly and slim as

always, touring guests through The Times and introducing me as his

favorite writer, good friend and personal car consultant.

Bald and pleasant overstatements. But in so doing, he turned his

importance over to me. Such was the deep and open-hearted kindness of

Jack Smith.

The first time we shared anything was a quarter-century earlier when he

was established, widely syndicated, and to Los Angeles what Herb Caen is

to San Francisco and Mike Royko to Chicago and Jimmy Breslin to New

York. A conscience, a muse, a crier.

I was trying to be the same to Phoenix, producing 800 nervous words a

day, five anxious days a week, as columnist for the Arizona Republic.

One reference caught Jack's eye and he called for permission to use it

in his column.

Me? You want something from my column? Only with your permission and

full credit. Which is about all we columnists get paid, he said.

We columnists. He had made an unknown his peer. Such was the simple

generosity and fellowship of Jack Smith.

We were never intimates in the sense of dinner parties and two seats at

Dodger games. But we were joined by sharing the persecutions and black

addiction of writing daily columns.

Jack believed and I agreed that it is the loneliest job in journalism.

Readers love you only when their biases match your opinions. Beat

reporters, once allies, show scorn because you have an office and are

semi-retired from risking death on dirty streets that give us this day

our daily grist.

Writing a column, I used to say, was living a soap opera. Lines are

learned one day, performed the next and immediately recycled for endless

tomorrows.

Jack quoted Marilyn Hudson, co-hostess of the Round Table West. She

believed a daily column is like making love to a nymphomaniac. When

you're finished and think you're through, you have to start all over

again.

Jack was a dinosaur in the most flattering sense of the word.

His prime was our best of times, somewhere between the crassness of

"Front Page" and the political correctness of "All the President's Men."

He evolved during an era when only editorial writers spoke political

arguments, theater critics were curmudgeons, and daily columnists were

expected to produce something called human interest.

What a calling a column was. It's where vignettes of a city find a

platform and a few hours of significance. A cop who could hurt despite

years of seeing it all. A child's triumph over an adult ill. Lost love.

Found fortune. A leg up for underdogs, a kick in the pants for fat cats,

and all in 800 words.

Jack Smith was a master of that and higher levels.

He crafted phrases and sculpted his column.

He played with words, skinny words, green words and pretty words, until

they giggled. He made us think by tweaking and chuckling, not thrashing

and cursing. Knowing his foibles made us feel better about not being

able to hang a screen door. He wrote of his bad heart and closing in on

death and then we knew how important dignity, gratitude and loved ones

are to whatever time we have left.

And if sometimes Los Angeles, its people and seedy corners seemed a

little brighter and warmer by his words, then maybe that's how our city

really is.

You may not have noticed everything. You may have read through the

intent of his past few months and thought that Jack Smith had finally

lost his fast ball.

No. He was chronicling his end. Because he accepted that a loyal legion

was diminishing and needed to know of his falls, of passing out among

friends, of throwing up on a cruise ship. By sharing his humiliations,

by forming a common damning of infirmity, maybe his old fans would be

less afraid.

In this, Jack took readers with him to the last breath.

The parade never really passed for Jack Smith. But it slowed,

inevitably, as he did. We spoke about dwindling days and changing times

during our last meeting and there was a sadness in his wry smile.

After a time of early retirements, employee buyouts and layoffs, Jack

felt a little uncomfortable visiting The Times. So many young writers.

Few old friends. Nobody seemed to know him. He could look around, he

said, and wonder if he ever worked here.

But he was happy to be writing one piece a week. It provided purpose and

kept a columnist's juices stirring. He still spent every day searching

for ideas. He still dreaded one day groping and finding nothing to

write.

Regrets at dropping a daily grind? Just one. Every day had been so much

damned fun it's a shame you don't get to do life over again.

Today's cynicism is to believe no person is irreplaceable. Jack Smith

is.

He even taught a younger writer instinct.

I'll bet this piece comes in just under 800 words.

***********************************************************************************

JACK SMITH

You Live With Sons, You Live With Their Creepy

Creatures

Life & Style, Page E-1

By JACK SMITH,

This was among Jack Smith's favorite pieces for the Los Angeles Times.

It appeared on March 2, 1954.

Any man blessed with a small boy of his own is certain to have his life

peopled, pardon the word, with live things. Not just comfortable beasts

one has learned to live with, like dogs and cats. We mean things of a

lower order. Slick gray things encountered in the garden under damp

leaves. Brown scaly things lifted lovingly from rocks. Wounded feathered

things.

Being blessed with not one but two small boys, we live in a fearsome and

ever-changing jungle, and no Hemingway us. We never know how many hearts

may beat beneath our roof at any given time. We walk the rugs lightly,

with eyes downcast, alert as any hunter, wary at the thought of treading

on some member of the family.

At night the house is alive with imagined sounds as we lie awake in the

dark. The infinitesimal inhale and exhale of who knows what; the pump

pumpeta pump of tiny yellow hearts. We ache to spring to the door and

lock it and build a campfire by the bed.

We can prove nothing. But, deep inside, we know. The voice of the

cricket. Does it come from outside the window? Or from down the hall.

That furtive scratching like a small wire dragged across the floor. We

will not investigate and play the fool. If we plunged into the heart of

the matter, and switched on the light, we would find only two boys

asleep in their beds with crafty dreamless faces; and nothing more

horrible than a soft movement under the covers, a sign that one had

smuggled in the cat again.

But nothing will relieve our uneasy feeling that somehow the balance of

nature has been tampered with in our own castle. Behind our back,

surreptitiously, nature's cycle has been spirited inside from out of

doors and goes on in its immemorial way within the cozy jungle of the

boys' bedroom, among the piles of toys. Procreation and birth and the

struggle for existence and death are accomplished while the boys see all

with wonderment and growing wisdom.

An amiable insect scrapes out his days at the bottom of a coffee can,

glutting on cookie crumbs and lettuce salvaged from the table, drenched

with oil and vinegar and garlic salt. Only to expire, finally, of old

age, or malaise de segment, or whatever kind of ill a bug is heir to. As

secretly as he came, then, he departs, his body borne in sorrow or

wonder or reverence to the earth from which he was borrowed by the boy.

Regarding us, of course, as the pestilence, the boys husband their

creatures with stealth, emerging from their crawling underworld to

confront the master of the house with empty hands and faces of sly

innocence. But now and then a word of evidence slips out, a name dropped

sotto voce in hurried conference. For all the beasts have names.

Squeakie, Brownie, Blackie, Superbug, Slimey, Shaggy. And only God and

the boys know what they mean. We are shaken, we tell you, when a name

like that is dropped in the household. Put yourself in our place, in an

all too usual crisis:

"Psst! [stage whispering] It's got away!"

"Are you sure?"

"Yes. It's not in the cigar box."

"Did you look under the leaves?"

"Uh-huh. Only Whiskers is there now."

"Maybe the rat got him."

"No. I know where the rat is."

"Where?"

"Under my shirt."

"Oh."

"Did you look in Daddy's bedroom?"

"Yeah. He wasn't there. Lizzie was, though."

That's enough, we say, for any man.

"BOYS!" we shout. "What in the name of. . . . WHAT'S got away?"

"Crispie."

"Crispie?"

"Uh-huh. He was in the cigar box."

"He's about this big and has. . . ."

"No, Doug. THIS big."

"Are you counting when he's curled up or when he spreads out?"

"BOYS! What in the name of. . . . What is this thing?"

"Well, I don't know exactly. It has six legs. I think.

"No, Curt. Eight legs. I counted."

"Some of those are feelers, Doug."

"Anyway, he only has two eyes."

"Thank God for that! All right boys, listen to me: You find that thing .

. . Crispie . . . whatever it is and GET IT OUT OF HERE!"

"All right, Daddy."

"All right, Daddy."

"Psst! Curt, look."

"Where?"

"There, on Daddy's chair."

"CRISPIE!"

You see?

***********************************************************************************

On Dentists, Rome, Aging . . .

and Saving Water

Life & Style, Page E-4

By BEVERLY BEYETTE, TIMES STAFF WRITER

Back in the '60s, Victoria Kling, an eighth-grader at Florence

Nightingale Junior High, won second prize in an essay contest on "My

Most Interesting Neighbor." Her subject: Jack Smith, who lived next door

on Mt. Washington:

Among Victoria's anecdotes about Mr. Smith, whom she described as "odd"

but "sincere":

"Last Christmas he put a star up on his roof and he hit himself in the

thumb with a screwdriver. My mother says you shouldn't say things like

he did when you're putting a star up on your roof."

Smith liked the essay so much that he asked her permission to use it as

the preface for his 1965 book, "Three Coins in the Birdbath."

Victoria, with the wisdom of a 13-year-old, had Jack Smith right: He was

Everyman--with his foibles and failings, with kids and goldfish and

hamsters. With a garage cluttered with castoffs and a penchant for doing

silly things like slamming a car door on his finger.

Upon his semi-retirement in January 1991, Smith reflected on 6,000

columns--maybe 5 million words. What was it all about? "It is about me

and living in Los Angeles. Consequently, I hoped, it would be about

everybody who lives in Los Angeles."

was it all about? "It is about me

and living in Los Angeles. Consequently, I hoped, it would be about

everybody who lives in Los Angeles."

Herewith, some Smith on Smith (the italicized passages are excerpted

from his writings):

* I sleep with my watch on because I like to know what time I dream a

particular dream. The trouble is, though, that I can't tell what time it

is without my glasses, and it's no good sleeping with your glasses on.

* On his attempts to avoid having a wisdom tooth yanked:

I tried changing dentists, never going back to the same one twice. But

they caught up with me. They have a conspiracy.

* On aging:

I've heard it said that men first begin to realize their youth is over

when policemen begin to look like college boys. That's true, but there's

a much more alarming sign, and that's when a man's doctors begin to die.

* Sometimes Jack Smith took perverse delight in being outrageous. He

delighted in the outraged reaction to the column in March, 1991, in

which he suggested an innovative way of conserving water in the

Southland:

I have hit upon a perfectly simple solution to this problem, one that I

recommend to all men. Instead of going to the bathroom, I simply go out

on the terrace and use my wife's garden. It is not only easy, it gives

me a refreshing moment in the outdoors, and there is the added bonus

that it irrigates the flowers.

* Some Jack Smith columns were provocative, some funny and, by his own

admission, "Many, of course, were dreadful"--the price of a daily

deadline.

* Acquiring a French daughter-in-law, Jacqueline, was a boon. "I

exploited the hell out of [her]," he acknowledged in an interview. Once,

he described her plundering his garden for escargots. Here, he explains

her taste in electronic entertainment as a newcomer to America:

[She] liked soap operas because everybody talked slow and said

everything twice.

Horror movies were Jacqueline's favorite TV fare. Her English still

wasn't quick enough to pick up all the thrusts and parries of fast

dialogue, and in that regard horror movies are even better than the soap

operas. They have very little dialogue at all, and it runs to freak and

creature talk, which is quite slow; or to Fay Wray screams and hoarse

cries of "My God, Dr. Peabody, it's come back!"

* When his sons, Douglas and Curtis, were young and he "didn't think

they could be damaged socially," they, too, were fair game.

I have discovered that the teenager's natural affinity for leisure

reaches its zenith when he is first infused by that phenomenon known as

the intellectual awakening. Overnight they drop their playthings and

pick up such bright baubles as Kierkegaard, Sartre, and Salinger. . . .

Once the muses have kissed the lad's brow it's hard to get him to do any

manual labor around the house at all. The spark that ignites the higher

brain centers seems to paralyze the back. . . . What father could summon

his child from a romp on Olympus with Whitman, Hemingway and Edna St.

Vincent Millay to mow an earthly lawn?

On enlisting Doug and Curt to recycle a sofa that was so disreputable it

was even rejected by the Salvation Army:

I offered the boys a dollar to get the ax and crowbar and dismember the

monster. They ripped it apart with demonic glee. We burned it in the

barbecue. It saved us on our charcoal bill, too, although some said the

hamburgers tasted like a chaise lounge. Anyway, it wasn't a complete

loss. We found 93 cents inside the sofa, plus four sticks of gum and a

Smith Bros. cough drop in medium-good condition. Also, later on the boys

made a bird cage out of the springs.

* Although Smith considered himself a proponent of women's rights, and

his wife, Denise, is a professional woman, he took great glee in

play-acting the role of male chauvinist. Consider this excerpt from a

piece describing his short-lived fantasy of moving to Rome. Denise had

been hesitant, explaining, "I don't have anything to wear." Smith tells

her:

You don't have to have any clothes, especially. You can stay home and

wash and sing out the window and make lasagna.

Ultimately, they decided not to move to Italy. Instead of writing "Three

Coins in the Fountain," a novel about Americans in Rome, he would stay

on Mt. Washington and pen "Three Coins in the Birdbath."

* Although Smith himself was, undeniably, a celebrity in his chosen

hometown, he was ill at ease among celebrities and "never knew what to

say" to them. Here, he describes a party at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel

in 1973, celebrating publication of Norman Mailer's "Marilyn":

[Mailer] stood in a slight crouch, feet apart, toes in, like a fighter;

a good middleweight, over the hill, but game. His pale-blue eyes seemed

alternately to burn and disconnect, as if his circuits were overloaded.

. . .

They [Mailer and Monroe] had never met in life, and here he was now,

revealing himself as her last, most passionate, most hopeless lover. . .

. They seemed an odd couple: Mailer so open, Marilyn so closed. He

should have called their book "The Naked and the Dead."

* Jack Smith, born in Long Beach, loved Los Angeles. With all its warts,

it was to him still a city of "wonders." Frequently, he found himself

defending it from its detractors, among them Woody Allen, who in his

1977 film "Annie Hall" claimed that the city's main contribution to

culture is that one can turn right on red.

What about the drive-in bank, the Frisbee, the doggie bag? Smith replied

to those who sneered at L.A. and its gifts to the world. What about our

Hansel and Gretel cottages, our Assyrian rubber factory, our

Beaux-Arts-Byzantine-Italian-Classic- Nebraska Modern City Hall? he

asked.

What about the drive-in church?

One can say a great deal for the Second Vatican Council, the discovery

of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Billy Graham crusades and the Jesus

Movement, but I suspect that the drive-in church will be seen from the

perspective of history as the greatest spur to the mid-20th-century

revival of Christianity. . . . Once it was demonstrated that we could do

business with God without getting out of our automobiles, there was no

reason to believe we couldn't also do business that way with Mammon.

***********************************************************************************

Jack Smith,

1916-1996

He loved his city, defending it

in print, boasting of it in private. And in return, Los Angeles embraced

Jack Smith. From the start in 1958, he was one of the few columnists who

could write about daily life--whether with his wife, sons and

grandchildren or as a combat correspondent in World War II--without

seeming desperate for material. His use of language was impeccable, his

manners flawless and his fascination with a changing world a constant

delight.

As a Young Man . . . Jack, circa 1918;

As a Young Man . . . visiting cousins in the country in the mid-'20s--Jack is on the right

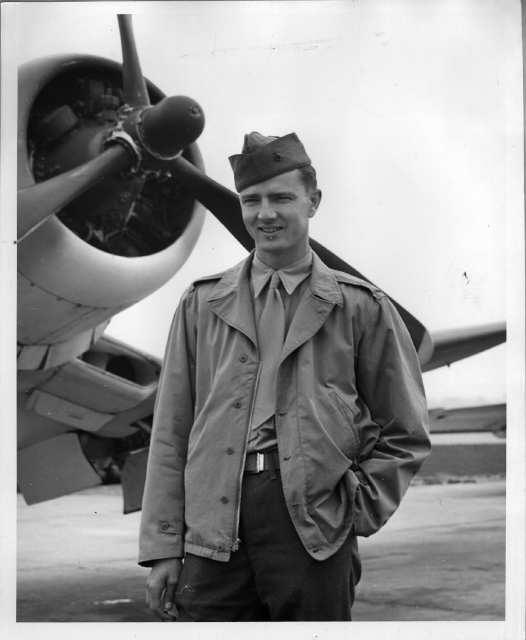

As a Young Man . . .a rakish young man in 1940.

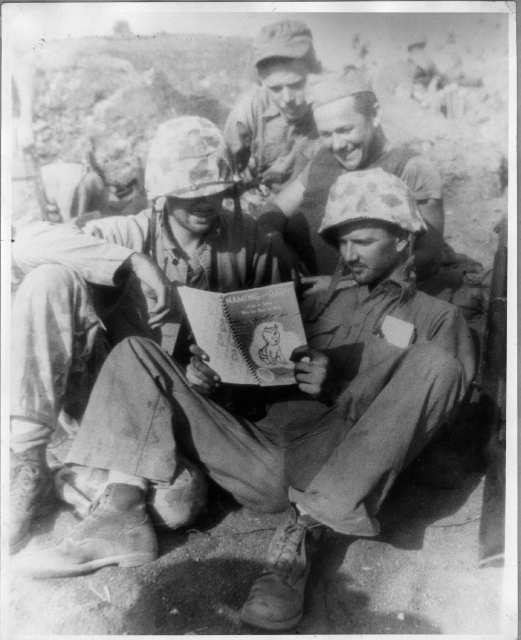

Military Man: On Iwo Jima, 1945, Jack scans a book of baby names sent to him by his wife before first son Curt's birth.

Family Man: The Smith family, circa 1952: Jack holding son Curt, wife Denny with Doug.

Denny and Jack just before Christmas 1995.

Denny and Jack just before Christmas 1995.

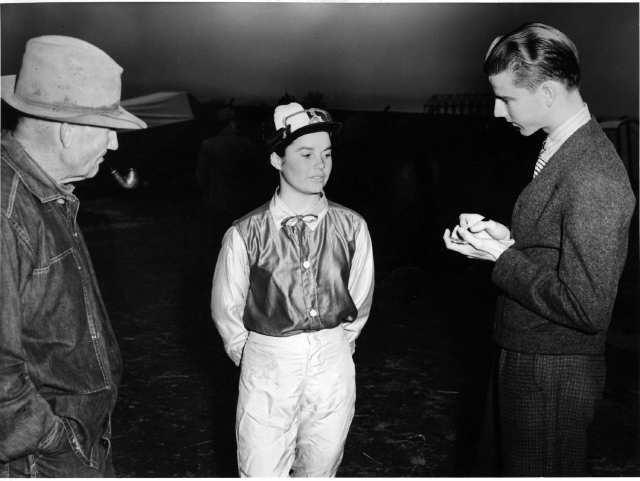

Newspaperman: Covering sports in 1938 in Bakersfield, where

he broke into the business;

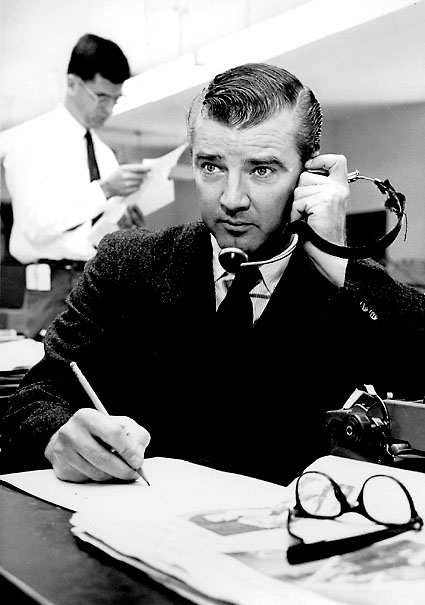

Doing rewrite at The Times, circa 1960

PHOTO CREDITS: Los Angeles Times and courtesy of the Smith family.

NOTE: Photos are uncropped archival versions and may differ from published versions.